Frankenstein

Frankenstein flees

"the creature"

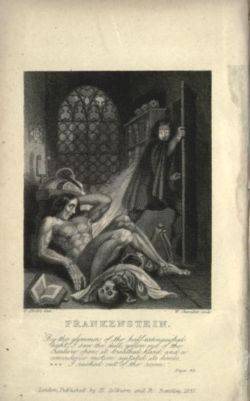

1831 edition, inside cover.

Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus is an 1818 novel written by Mary Shelley at the age of 19, first

published anonymously in London, but more often known by the revised third

edition of 1831 under her own name. It is a novel infused with some elements of

the Gothic novel and the Romantic movement. It was also a warning

against the "over-reaching" of modern man and the Industrial

Revolution, alluded to in the novel's subtitle, The Modern Prometheus.

The story has had an influence across literature and popular culture and

spawned a complete genre of horror stories and films.

Shelley's Inspiration

During the snowy summer

of 1816, the world was locked in a long cold volcanic winter caused by the

eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815. In this terrible year, Mary Wollstonecraft

Godwin, age 19, and her lover (and later husband) Percy Bysshe Shelley,

visited Lord Byron at Lake Geneva in Switzerland. The weather was

consistently too cold and dreary that summer to enjoy the outdoor vacation

activities they had planned, so after reading Fantasmagoriana, an

anthology of German ghost stories, Byron challenged the Shelleys and his

personal physician John William Polidori to each compose a story of their own, the

contest being won by whoever wrote the scariest tale. Mary conceived an

idea after she fell into a waking dream or nightmare during which she saw

"the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put

together." This was the germ of Frankenstein. Byron managed to

write just a fragment based on the vampire legends he heard while travelling

the Balkans, and from this Polidori created The Vampyre (1819), the

progenitor of the romantic vampire literary genre. Thus, the Frankenstein and

vampire themes were created from that single circumstance.

Name origins

The creature

Part of Frankenstein's

rejection of his creation is the fact that he doesn't give it a name,

which gives it a lack of identity. Instead it is referred to by words

such as 'monster', 'creature', 'dæmon', 'fiend', and 'wretch'. When

Frankenstein converses with the monster in chapter 10, he addresses it as

'Devil', 'Vile insect', 'Abhorred monster', 'fiend', 'wretched devil' and

'abhorred devil'. During a telling she did of Frankenstein, she referred to the

creature as "Adam". It is not known for sure, but it is likely

that Shelly is referring to the first man in the Garden of Eden here, as

her epigraph:

'Did I request thee,

Maker from my clay

To mould Me man? Did I

solicit thee

From darkness to promote

me?'

- (X.743-5), John

Milton's Paradise Lost.

The monster has often been mistakingly called

"Frankenstein". In 1908 one author said "It is strange to note

how well-nigh universally the term "Frankenstein" is misused, even by

intelligent persons, as describing some hideous monster...". After the release of James Whale's popular

1931 film Frankenstein, the public at large began speaking of the

monster itself as "Frankenstein". Some justify referring to the

Creature as "Frankenstein" by pointing out that the Creature is, so

to speak, Victor Frankenstein's offspring. Another interpretation is that it is

Frankenstein himself who is the monster, because of his savage rejection of the

being he created. Although Victor has very few pangs of conscience regarding

his duty towards the creature he brought to life, it is his undeserved neglect

that causes the creature to turn to evil. In a moral, if not actual sense, it

is indeed Victor who is the monster.

Frankenstein

Mary Shelley always

maintained that she derived the name "Frankenstein" from a

dream-vision, yet despite these public claims of originality, the name and what

it means has been a source of many speculations. Frankenstein is a common

family name in Germany. Literally, in German, the name Frankenstein

means stone of the Franks. The word "frank" means also

"free" in the sense of "not being subject to".

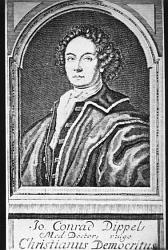

There is also a town called Frankenstein and a Frankenstein Castle

near Darmstadt which Shelley had seen whilst on a boat before writing the

novel. Some believe that Mary and Percy Shelley visited Castle Frankenstein on

their way to Switzerland, where a notorious alchemist named Konrad

Dippel had experimented with human bodies, but that Mary suppressed

mentioning this visit, to maintain her public claim of originality.

Victor

A possible

interpretation of the name Victor derives from the poem Paradise Lost

by John Milton, a great influence on Shelley (a quotation from Paradise

Lost is on the opening page of Frankenstein and Shelley even allows

the monster himself to read it). Milton frequently refers to God as

"the Victor" in Paradise Lost, and Shelley sees Victor as

playing God by creating life. In addition to this, Shelley's portrayal of

the monster owes much to the character of Satan in Paradise Lost;

indeed, the monster says, after reading the epic poem, that he sympathizes with

Satan's role in the story.

Victor was also a pen

name of Percy Shelley's, as in the collection of

poetry he wrote with his sister Elizabeth, Original Poetry by Victor and

Cazire. There is speculation that one of Mary Shelley's models for

Victor Frankenstein was Percy, who at Eton had "experimented with

electricity and magnetism as well as with gunpowder and numerous chemical

reactions," and whose rooms at Oxford were filled with scientific

equipment.

"Modern

Prometheus"

The Modern Prometheus is the novel's subtitle (though some modern publishings of the work now

drop the subtitle, mentioning it only in an introduction). Prometheus,

in some versions of Greek mythology, was the Titan who created mankind,

and Victor's work by creating man by new means obviously reflects that creative

work. Prometheus was also the bringer of fire who took fire from

heaven and gave it to man. Zeus eternally punished Prometheus by fixing

him to a rock where each day a predatory bird came to devour his liver, only

for the liver to return again on the next day; ready for the bird to come again.

Prometheus was also a myth told in Latin but was a very different story. In this version Prometheus makes man from clay and water, again a very relevant theme to Frankenstein as Victor rebels against the laws of nature and as a result is punished by his creation.

Prometheus' relation to

the novel can be interpreted in a number of ways. For Mary Shelley on a

personal level, Prometheus was not a hero but a devil, whom she blamed for

bringing fire to man and thereby seducing the human race to the vice of eating

meat (fire brought cooking which brought hunting and killing). For Romance era

artists in general, Prometheus' gift to man compared with the two great utopian

promises of the 18th century: the Industrial Revolution and the French

Revolution, containing both great promise and potentially unknown horrors.

Byron was particularly

attached to the play Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, and Percy Shelley

would soon write Prometheus Unbound. The term "Modern Prometheus"

was actually coined by Immanuel Kant, referring to Benjamin Franklin and

his then recent experiments with electricity. Clearly, a phonetic link

between "Franklin" and "Frankenstein" can be

observed, and Shelley would have been well aware of Franklin's work.

Analysis

Frankenstein is in some ways allegorical. The novel was conceived and written

during an early phase of the Industrial Revolution, at a time of dramatic

advances in science and technology. That the creation rebels against its

creator can be seen as a warning that the application of science can lead to

unintended consequences.

Another interpretation

was alluded to by Shelley herself, in her account of the radical politics

of William Godwin, her father:

|

“ |

The

giant now awoke. The mind, never torpid, but never roused to its full

energies, received the spark which lit it into an unextinguishable flame. Who

can now tell the feelings of liberal men on the first outbreak of the French

Revolution. In but too short a time afterwards, it became tarnished by the

vices of Orléans -- dimmed by the want of talent of the Girondists --

deformed and blood-stained by the Jacobins. |

” |

Clearly, Shelley herself thinks that the best

intentions of men quickly become corrupt and monstrous in revolutionary

politics.

A common critique views

the story as a journey of pregnancy. The novel taps into the widespread

fears of stillborn births and maternal deaths due to

complications in delivery - Shelley had suffered a stillborn birth in the prior

year, and her mother had died due to complications from her birth. Frankenstein

-- the Monster's parent, in a sense -- is fearful of the release of the Monster

from his control, when it is free to act independently in the world and affect

it for better or worse. Also, during much of the novel, Victor fears the

creature's desire to destroy him by killing everyone and everything most dear

to him. However, it must be noted that the creature was not born evil, but

only wanted to be loved by its creator, by other humans, and to love a sentient

creature like itself. It was mankind who taught it evil: Victor rejected

it, and the creature's poor treatment by villagers taught it how to be evil. In

this reading, the creature represents the natural fears of bringing a new

innocent life into the world and raising it properly so that it does not become

a monster.

The book can be seen as

a criticism of scientists who are unconcerned by the potential consequences of

their work. Victor was heedless of those dangers, and

irresponsible with his invention. Instead of immediately destroying the evil he

had created, he was overcome by fear and fell psychologically ill.

During Justine's trial for murder, he had the chance to come forth and protest

to the fact that a violent man had recently declared a vendetta against him and

his loved ones, thus saving the young girl. Instead, Frankenstein indulges

in his own self-centered grief. The day before Justine is executed and thus

resigns herself to her fate and departure from the "sad and bitter

world", his sentiments are as such:

|

“ |

The

poor victim, who was on the morrow to pass the awful boundary between life

and death, felt not, as I did, such deep and bitter agony...The tortures of

the accused did not equal mine; she was sustained by innocence, but the fangs

of remorse tore my bosom and would not forego their hold. |

” |

Some scholars believe that Mary Shelley's intent was for the reader to understand that the Creature never existed, and Victor Frankenstein committed the three murders. In this interpretation, the story is a study of the moral degradation of Victor, and the "science-fiction" aspects of the story are Victor's imagination.

Alchemy was a very popular topic in Shelley's world. In fact, it was becoming

an acceptable idea that humanity could infuse the spark of life into a

non-living thing (Luigi Galvani's experiments, for example). The

scientific world just after the Industrial Revolution was delving into

the unknown, and limitless possibilities also caused fear and apprehension for

many as to the consequences of such horrific possibilities.

The book also considers the ethics of creating life and contains innumerable biblical allusions in this context.

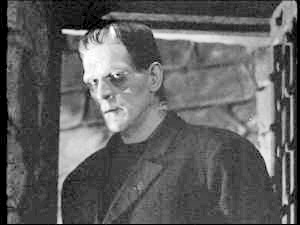

Boris Karloff as Frankenstein's Monster

In the 1931 film

"Frankenstein," Boris Karloff plays the part of the Creature,

and the scientist, played by Colin Clive, is renamed Henry Frankenstein.

Shelley's character Henry Clerval does not appear in the film at all,

which eliminates Victor's foil altogether. However, there is a

character called Victor who is after Elizabeth, Frankenstein's fiancee. Changing

the doctor's name from Victor also eliminates some original irony, inasmuch as

the novel ends after exposing the doctor's utter failure and destruction. Since

this film, the horror culture has confused modern audiences into placing the

scientist's name to his freakish creation. This event has stimulated much

conversation in the literary criticism of Shelley's work. Attributing the name

of the scientist to his creation reveals a deeper connection between the two,

especially when the scientist realizes the great danger that the creation

presents to himself and to the world.

Mary Shelley's Sources

Mary incorporated a

number of different sources into her work, not the least of which was the Promethean

myth from Ovid. The influence of John Milton's Paradise Lost,

and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,

being the books the creature finds in the cabin, are also clearly evident

within the novel. Frankenstein also contains multiple references to her

mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, and her major work A Vindication of

the Rights of Woman which discusses the lack of equal education for

males and females. The inclusion of her mother's ideas in her work is also

related to the theme of creation/motherhood in the novel. Mary is likely

to have acquired some ideas for Frankenstein’s character from Humphry Davy’s

book Elements of Chemical Philosophy in which he had written: "science

has… bestowed upon man powers which may be called creative; which have enabled

him to change and modify the beings around him…".

Themes, Motifs & Symbols

Themes

Themes are the fundamental and often universal ideas

explored in a literary work.

Dangerous

Knowledge

The pursuit of knowledge is at the

heart of Frankenstein, as Victor attempts to surge beyond accepted

human limits and access the secret of life. Likewise, Robert Walton attempts to

surpass previous human explorations by endeavoring to reach the North

Pole. This ruthless pursuit of knowledge, of the light (symbolically as

“Light and Fire”), proves dangerous, as Victor’s act of creation eventually

results in the destruction of everyone dear to him, and Walton finds

himself perilously trapped between sheets of ice. Whereas Victor’s obsessive

hatred of the monster drives him to his death, Walton ultimately pulls back

from his treacherous mission, having learned from Victor’s example how

destructive the thirst for knowledge can be.

Sublime Nature

The sublime natural world, embraced by Romanticism

(late eighteenth century to mid-nineteenth century) as a source of unrestrained

emotional experience for the individual, initially offers characters the

possibility of spiritual renewal. Mired in depression and remorse after

the deaths of William and Justine, for which he feels responsible, Victor heads

to the mountains to lift his spirits. Likewise, after a hellish winter of cold

and abandonment, the monster feels his heart lighten as spring arrives. The influence

of nature on mood is evident throughout the novel, but for Victor, the

natural world’s power to console him wanes when he realizes that the monster

will haunt him no matter where he goes. By the end, as Victor chases the

monster obsessively, nature, in the form of the Arctic desert,

functions simply as the symbolic backdrop for his primal struggle against the

monster.

Monstrosity

Obviously, this theme pervades the entire

novel, as the monster lies at the center of the action. Eight feet tall and

hideously ugly, the monster is rejected by society. However, his

monstrosity results not only from his grotesque appearance but also from the unnatural

manner of his creation, which involves the secretive animation of a mix of

stolen body parts and strange chemicals. He is a product not of collaborative

scientific effort but of dark, supernatural workings.

The monster is only the most literal of a number of monstrous

entities in the novel, including the knowledge that Victor used to create the

monster. One can argue that Victor himself is a kind of monster, as his

ambition, secrecy, and selfishness alienate him from human society.

Ordinary on the outside, he may be the true “monster” inside, as he is

eventually consumed by an obsessive hatred of his creation. Finally, many

critics have described the novel itself as monstrous, a stitched-together

combination of different voices, texts, and tenses.

Secrecy

Victor conceives of science as a mystery to

be probed; its secrets, once discovered, must be jealously guarded. He

considers M. Krempe, the natural philosopher he meets at Ingolstadt, a model

scientist: “an uncouth man, but deeply imbued in the secrets of his science.”

Victor’s entire obsession with creating life is shrouded in secrecy, and his

obsession with destroying the monster remains equally secret until Walton hears

his tale.

Whereas Victor continues in his secrecy

out of shame and guilt, the monster is forced into seclusion by his grotesque

appearance. Walton serves as the final confessor for both, and their tragic

relationship becomes immortalized in Walton’s letters. In confessing all just

before he dies, Victor escapes the stifling secrecy that has ruined his life;

likewise, the monster takes advantage of Walton’s presence to forge a human

connection, hoping desperately that at last someone will understand, and

empathize with, his miserable existence.

Texts

Frankenstein is overflowing

with texts: letters, notes, journals, inscriptions, and books

fill the novel, sometimes nestled inside each other, other times simply alluded

to or quoted. Walton’s letters envelop the entire tale; Victor’s story fits

inside Walton’s letters; the monster’s story fits inside Victor’s; and the love

story of Felix and Safie and references to Paradise

Lost fit inside the monster’s story. This profusion of texts is an

important aspect of the narrative structure, as the various writings serve as

concrete manifestations of characters’ attitudes and emotions.

Language plays an enormous role in the

monster’s development. By hearing and watching the peasants, the monster learns

to speak and read, which enables him to understand the manner of his creation,

as described in Victor’s journal. He later leaves notes for Victor along the

chase into the northern ice, inscribing words in trees and on rocks, turning

nature itself into a writing surface.

Motifs

Motifs are recurring structures, contrasts, or literary

devices that can help to develop and inform the text’s major themes.

Passive Women

For a novel written by the daughter of an

important feminist, Frankenstein is

strikingly devoid of strong female characters. The novel is littered with

passive women who suffer calmly and then expire: Caroline Beaufort

is a self-sacrificing mother who dies taking care of her adopted daughter; Justine

is executed for murder, despite her innocence; the creation of the female

monster is aborted by Victor because he fears being unable to control her

actions once she is animated; Elizabeth waits, impatient but helpless,

for Victor to return to her, and she is eventually murdered by the monster. One

can argue that Shelley renders her female characters so passive and subjects

them to such ill treatment in order to call attention to the obsessive and

destructive behavior that Victor and the monster exhibit.

Abortion

The motif of abortion recurs as both

Victor and the monster express their sense of the monster’s hideousness. About first

seeing his creation, Victor says: “When I thought of him, I gnashed my teeth,

my eyes became inflamed, and I ardently wished to extinguish that life which

I had so thoughtlessly made.” The monster feels a similar disgust for

himself: “I, the miserable and the abandoned, am an abortion, to be spurned

at, and kicked, and trampled on.” Both lament the monster’s existence

and wish that Victor had never engaged in his act of creation.

The motif appears also in regard to Victor’s other pursuits. When Victor destroys his work on a female monster, he literally aborts his act of creation, preventing the female monster from coming alive. Figurative abortion materializes in Victor’s description of natural philosophy: “I at once gave up my former occupations; set down natural history and all its progeny as a deformed and abortive creation; and entertained the greatest disdain for a would-be science, which could never even step within the threshold of real knowledge.” As with the monster, Victor becomes dissatisfied with natural philosophy and shuns it not only as unhelpful but also as intellectually grotesque.

Symbols

Symbols are objects,

characters, figures, or colors used to represent abstract ideas or concepts.

Light and Fire

“What could not be expected in the

country of eternal light?” asks Walton, displaying a faith in, and optimism

about, science. In Frankenstein, light symbolizes knowledge,

discovery, and enlightenment. The natural world is a place of dark secrets,

hidden passages, and unknown mechanisms; the goal of the scientist is then

to reach light. The dangerous and more powerful cousin of light is fire.

The monster’s first experience with a still-smoldering flame reveals the

dual nature of fire: he discovers excitedly that it creates light in the

darkness of the night, but also that it harms him when he touches it.

The presence of fire in the text also

brings to mind the full title of Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein:

or, The Modern Prometheus. The Greek god Prometheus gave the

knowledge of fire to humanity and was then severely punished for it. Victor,

attempting to become a modern Prometheus, is certainly punished, but unlike

fire, his “gift” to humanity—knowledge of the secret of life—remains a secret.

Gothic fiction

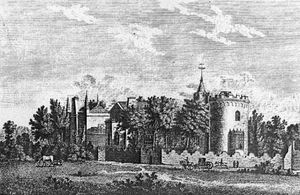

Strawberry Hill, an English villa in the

"Gothic revival" style, built by seminal Gothic writer Horace Walpole

Gothic fiction is a genre of literature that combines elements of both horror and

romance. As a genre, it is generally believed to have been invented by the

English author Horace Walpole, with his 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto.

The effect of Gothic fiction depends on a pleasing sort of terror.

Prominent features of

Gothic fiction include terror (both psychological and physical), mystery,

the supernatural, ghosts, haunted houses and Gothic architecture, castles,

darkness, death, decay, doubles, madness, secrets and hereditary curses.

The stock characters

of Gothic fiction include tyrants, villains, bandits, maniacs, Byronic

heroes, persecuted maidens, femmes fatales, madwomen, magicians, vampires,

werewolves, monsters, demons, revenants, ghosts, perambulating skeletons, and

the Devil himself.

Important ideas

concerning and regarding the Gothic include: Anti-Catholicism,

especially criticism of Roman Catholic excesses such as the Inquisition

(in southern European countries such as Italy and Spain); romanticism of

an ancient Medieval past; melodrama; and parody (including

self-parody).

Origins

The term

"Gothic" was originally used to criticize a certain kind of

architecture and art. Gothic architecture became popular in the nineteenth

century. The term "gothic" became linked with an appreciation

of the joys of extreme emotion, the thrill of fearfulness and awe

inherent in the sublime, and a quest for atmosphere. English

Protestants often associated medieval buildings with what they saw as a dark

and terrifying period, characterized by harsh laws enforced by torture, and

with mysterious, fantastic and superstitious rituals.

The First Gothic Romances

The term

"Gothic" came to be applied to the literary genre precisely because

the genre dealt with such emotional extremes and very dark themes,

and because it found its most natural settings in the buildings of this style —

castles, mansions, and monasteries, often remote, crumbling, and ruined.

It was a fascination with this architecture and its related art, poetry, and

even landscape gardening that inspired the first wave of gothic novelists.

It was Ann Radcliffe who

created the gothic novel in its now-standard form. Among other elements,

Radcliffe introduced the brooding figure of the gothic villain, which

developed into the Byronic hero. A Byronic hero is:

|

an idealized but flawed character

exemplified in the life and writings of Lord Byron, who is "mad,

bad and dangerous to know". The Byronic hero has the following

characteristics: ·

conflicting emotions and moodiness ·

self-critical and introspective ·

struggles with integrity ·

a distaste for social institutions and social

norms ·

being an exile, an outcast, or an outlaw ·

a lack of respect for rank and privilege ·

a troubled past ·

being cynical, demanding, and/or arrogant ·

often self-destructive ·

loner, often rejected from society |

Ann Radcliffe’s gothic

novels were best-sellers, although along with all novels they were looked down

upon by well-educated people as sensationalist women's entertainment (despite

some men's enjoyment of them).

The

Romantics

Further contributions to

the Gothic genre were provided in the work of the Romantic poets.

Lord Byron’s work created the Byronic hero.

Mary Shelley's novel, Frankenstein, though clearly influenced by the

gothic tradition, is often considered the first science fiction novel,

despite the omission in the novel of any scientific explanation of the

monster's animation and the focus instead on the moral issues and consequences

of such a creation.

Victorian

Gothic

The greatest

re-interpreter of the Gothic in this period was Edgar Allan Poe who

opined 'that terror is not of Germany, but of the soul’. His story "The

Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) explores these 'terrors of the

soul' whilst revisiting classic Gothic tropes of aristocratic decay, death and

madness. The legendary villainy of the Spanish Inquisition, previously explored

by Gothicists Radcliffe, Lewis and Maturin, is revisited in "The Pit

and the Pendulum" (1842). The influence of Byronic Romanticism evident

in Poe is also apparent in the work of the Bronte sisters. Emily Brontë's

Wuthering Heights (1847) transports the Gothic to the forbidding

Yorkshire Moors and features ghostly apparitions and a Byronic anti-hero in the

person of the demonic Heathcliff whilst Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre

(1847) adds the madwoman in the attic to the cast of gothic fiction. The

Brontë's fiction is seen by some feminist critics as prime examples of Female

Gothic, exploring woman's entrapment and subjection to men, as well as the

attempts of women to escape from these unequal and subordinate positions.

Romanticism

Wanderer above the sea of fog by

Caspar David Friedrich

Romanticism is an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in 18th century Western Europe, around 1790, during the Industrial Revolution. It was partly a revolt against the order of society during the Enlightenment period, but it also was a reaction against the new idea that the scientific method was the only way to understand things, or to get at the truth. Emotions, during the Enlightenment, were thought to get in the way of true understanding. Where science stressed logic and method, romanticism stressed emotion and feeling as the real way to understand things. Science and technology had gone hand in hand during the Industrial Revolution to conquer and to master nature. The natural world’s beauty wasn’t important to the industrialist; however, romantics stressed the importance of feeling the strong emotions that arise from being in the natural world and experiencing its beauty and power. Romantics therefore placed a new emphasis on such emotions as trepidation, horror, and the awe experienced in confronting the sublimity of untamed nature. Where the industrialists and modern scientists looked to scientific discoveries and new technologies for a knowledge that can master the world, romantic authors elevated old traditions, the simple life apart from the industrial world, folk art, nature and custom. The term "romantic" itself comes from the word "romance" which is a prose or poetic heroic narrative originating in medieval literature and romantic literature. Romance is the emotion of the heart.

Many people have seen Romanticism

as a key movement in the Counter-Enlightenment, a reaction against the Age

of Enlightenment. Whereas the thinkers of the Enlightenment

emphasized the primacy of reason, logic, and rational thought, Romanticism

emphasized intuition, imagination, and feeling, to a point that has led to some

Romantic thinkers being accused of irrationalism.

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of was an

eighteenth century movement which held that reason, rational inquiry, or

thought ought to be the primary basis of authority. The era is generally agreed

to have ended around the year 1800 and the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars

(1804-15).

The Enlightenment

is often closely linked with the Scientific Revolution, for both movements

emphasized reason, science, and rationality, while the former also sought their

application in comprehension of divine or natural law. Enlightenment

thinkers believed that systematic thinking might be applied to all areas of

human activity. Its leaders believed they could lead their states to progress

after a long period of tradition, irrationality, superstition, and tyranny

which they imputed to the Middle Ages.

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial

Revolution was a major shift of technological, socioeconomic, and cultural

conditions that occurred in the late 18th century and early 19th century in some

Western countries. It began in Britain and spread throughout the world, a

process that continues as industrialisation. The onset of the Industrial

Revolution marked a major turning point in human social history, comparable to

the invention of farming or the rise of the first city-states; almost every

aspect of daily life and human society is, eventually, in some way influenced.

Manchester, England ("Cottonopolis"), pictured in 1840, showing the mass of factory chimneys

Industrialisation led to

the creation of the factory. The factory system was

largely responsible for the rise of the modern city, as workers migrated into

the cities in search of employment in the factories. Nowhere was this

better illustrated than the mills and associated industries of Manchester,

nicknamed Cottonopolis, and arguably the world's first industrial city.

A Watt steam engine, the steam engine that

propelled the Industrial Revolution in Britain and the world.

In the latter half of

the 1700s, the manual labour based economy of the Britain began to be

replaced by one dominated by industry and the manufacture of machinery. It

started with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of

iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Trade expansion

was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. The

introduction of steam power (fuelled primarily by coal) and powered

machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic

increases in production capacity. The development of all-metal machine

tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture

of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects

spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century,

eventually affecting most of the world. The impact of this change on society

was enormous.

Social effects

In terms of social

structure, the Industrial Revolution witnessed the triumph of a

middle class of industrialists and businessmen over a landed class of nobility

and gentry. Ordinary working people found increased opportunities for

employment in the new mills and factories, but these were often under strict

and very harsh working conditions with long hours of labour dominated by a pace

set by machines. However, harsh working conditions were prevalent long

before the industrial revolution took place as well. Pre-industrial society was

very static and often cruel—child labour, dirty living conditions

and long working hours were just as prevalent before the Industrial

Revolution.

Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus,

whose name literally means “forethought,” is the Titan chiefly

honored for stealing fire from Zeus in the stalk of a fennel plant and

giving it to mortals for their use. For that, Zeus ordered him to be chained on

top of the Caucasus. Every day an eagle would come and eat his liver, but since

Prometheus was immortal, his liver always grew back, so he was left to

bear the pain every day. He is depicted as an intelligent and cunning figure

who had sympathy for humanity. To this day, the term Promethean refers

to events or people of great creativity, intellect, and boldness.

The Myth

Prometheus was a son of

Iapetus by Clymene (one of the Oceanids). He was also a brother of Atlas,

Menoetius and Epimetheus, but he surpassed all in cunning and deceit. He

held no awe for the gods, and he ridiculed Zeus, although he was favored by him

for his assistance in the fight against Cronus.

Prometheus, in Ovid's Metamorphoses,

is credited with the creation of man "in godlike image" from clay

(in others, this role is assigned to Zeus). When he and his brother Epimetheus

(whose name means “afterthought”) set out to make creatures to populate

the earth under the orders of Cronus, Prometheus carefully crafted a

creature after the shape of the gods: a man. According to the myths, a

horrendous headache overcame Zeus and no healer of the realm was able to help

the lord of the gods. Prometheus came to him and declared that he knew how to

heal Zeus. Taking a rock from the ground, Prometheus proceeded to hit Zeus on

the head with it. From out of Zeus' head popped the goddess Athena, the

goddess of wisdom and warfare; with her emergence Zeus' headache disappeared.

Some myths attribute Hephaestus or Hera to the splitting of the

head rather than Prometheus.

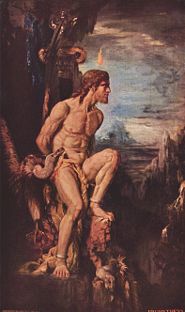

Prometheus by Gustave Moreau, (1868).

Prometheus and Epimetheus

journeyed to Earth from Olympus, then ventured to the Greek province of Boitia

and made clay figures. Zeus took the figures and breathed life into

them. The figures that Prometheus had created became Man and honored him.

The figures that his brother Epimetheus had created became the beasts, which

turned and attacked him.

Prometheus brings Fire to Mankind, by

Heinrich Füger, (1817).

Zeus was angered by the brothers' actions; he

forbade the pair from teaching Man the ways of civilization. Athena chose to

cross Zeus and taught Prometheus so that he might teach Man.

For their actions, Zeus demanded a sacrifice

from man to the gods to show that they were obedient and worshipful. The

gods and mortal man had arranged a meeting at Mecone where the matter of

division of sacrifice was to be settled. Prometheus slew a large ox, and

divided it into two piles. In one pile he put all the meat and most of the fat,

skillfully covering it with the ox's grotesque stomach, while in the other

pile, he dressed up the bones artfully with shining fat.

Prometheus then invited

Zeus to choose. Zeus chose the pile of bones, and was angered to find that he

had been tricked. In Hesiod's Theogony, Zeus saw through the

trick, but still chose the pile of bones because he realized that in

purposefully getting tricked he would have an excuse to vent his anger on

mortal man. This also gives a mythological explanation of the practice of

sacrificing only the bones to the gods, while man gets to keep the meat and

fat.

Zeus in his wrath denied

men the secret of fire. Prometheus felt sorry for his

creations, and watched as they shivered in the cold and winter's nights. He

decided to give his most loved creation a great gift that was a "good

servant and bad master". He took fire from the hearth of the gods by

stealth and brought it to men in a hollow wand of fennel, or ferule that

served him instead of a staff. He brought down the fire coal and gave it to

man. He then showed them how to cook and stay warm. To punish Prometheus for

this overweening pride or hubris (and all of mankind in

the process), Zeus devised "such evil for them that they shall desire

death rather than life, and Prometheus shall see their misery and be powerless

to succor them. That shall be his keenest pang among the torments I will heap

upon him." Zeus could not just take fire back, because a god or goddess

could not take away what the other had given.

To punish man for the

offenses of Prometheus, Zeus told Hephaestus to "mingle together all

things loveliest, sweetest, and best, but look that you also mingle therewith

the opposites of each." So Hephaestus took gold and

dross, wax and flint, pure snow and mud of the highways, honey and gall; he

took the bloom of the rose and the toad's venom, the voice of laughing water

and the peacocks squall; he took the sea's beauty and its treachery, the dog's

fidelity and the wind's inconstancy, and the mother bird's heart of love and

the cruelty of the tiger. All these, and other contraries past number, he

blended cunningly into one substance and this he molded into the shape that

Zeus had described to him. She was as beautiful as a goddess and Zeus named her

Pandora which meant "all gifted".

Zeus breathed upon her

image, and it lived. Zeus sent her to wed Prometheus' brother, Epimetheus,

and although Prometheus had warned his brother never to accept gifts from the

Olympians, Epimetheus was love-stricken, and he and Pandora wed. The Gods

adorned the couple with many wedding gifts, and Zeus presented them with a beautifully

made box. When Pandora opened the box, all suffering and despair was

unleashed upon mankind. Zeus had had his revenge.

Zeus was enraged because

the giving of fire began an era of enlightenment for Man, and had

Prometheus carried to Mount Caucasus, where an eagle by the name of Ethon

would pick at his liver; it would grow back each day and the eagle would eat it

again. Curiously, the liver is one of the rare human organs to regenerate

itself spontaneously in the case of lesion.

In some stories, such as

Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound, Zeus has Prometheus tortured on the

mountain because he knows the name of the person who, according to prophecy,

will overthrow the king of the gods. This punishment was to last 30,000 years.

About 12 generations later, Heracles (known as Hercules in Roman

mythology), passing by on his way to find the apples of the Hesperides as

part of the Twelve Labours, freed Prometheus. Once free, Prometheus

captured the eagle and ate his liver as revenge for his pain and suffering.

Zeus did not mind this time that Prometheus had again evaded his punishment, as

the act brought more glory to Heracles, who was Zeus's son. However, there was

a problem: Zeus had made the decision that Prometheus would be tied in the rock

for eternity. According to Greek mythology, this could never change, even if

Zeus himself wished it. Finally, a solution was found. Prometheus was invited

to return to Olympus and was given a ring by Zeus which contained a piece of

the rock to which Prometheus had been bound. Prometheus liked this

ring and decided to wear it thereafter for eternity. According to some myths,

Hercules was told by Zeus to tell Prometheus the solution.

As the introducer of

fire and inventor of crafts, Prometheus was seen as the patron of human

civilization. Uncertain sources claim he was worshiped in

ancient Rome as well, along with other gods.

Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley (30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English romantic/gothic novelist

and the author of Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. She was

married to the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Biography

Mary

Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in Somers

Town, in London, in 1797. She was the second daughter of famed feminist,

educator and writer Mary Wollstonecraft. Her father was the equally

famous anarchist philosopher, novelist, journalist, and atheist dissenter, William

Godwin. Her mother died ten days after Mary was born as a result of

puerperal fever.

Godwin had long realized

that he could not raise his daughters by himself, and had been actively looking

for a second wife. After courting a number of women, he met Mary Jane

Clairmont, a widow with two young children. He soon fell in love with her

and married her, although his friends did not approve of the match. Mary Jane

Clairmont was a difficult woman with a quick temper and a sharp tongue, and she

quarrelled frequently with her husband. She did not get on well with her

step-daughters, especially Mary whose attachment to Godwin she resented. She

also disliked the amount of attention that Mary, as the daughter of the two

most famous radicals of the time, received from visitors to the Godwin

household. Although she took care of Mary's physical needs, ensuring that she

was fed and clothed, and nursing her when she was ill, she neglected her

spiritual and mental ones. She made Mary do many of the household chores, invaded

her privacy, and restricted her access to her father. She also ensured that her

own daughter, Jane Clairmont received more education than Mary Godwin.

Nonetheless, despite her

stepmother's efforts, Mary received an excellent education, which was

unusual for girls at the time. She never went to school, but she was

taught to read and write, and then educated in a broad range of subjects by her

father who gave her free access to his extensive library. In particular,

she was encouraged to write stories. At the same time, Godwin allowed her to

listen to the conversations he had with many of the leading intellectuals and

poets of the day.

By 1812, the animosity

between Mary and her step-mother had grown to such an extent that William

Godwin sent her to board with an acquaintance, William Baxter, who lived in

Scotland. Mary's stay with the Baxter family had a profound effect on her: they

provided her with a model of the type of closely-knit, loving family to

which she would aspire for the rest of her life. Moreover, in the 1831 Preface

to Frankenstein, she claims that this period of life led to her

development as a writer.

On a visit home in 1812,

she met Percy Bysshe Shelley, a political radical and free-thinker like

her father, when Percy and his first wife Harriet visited Godwin's home and

bookshop in London. By 1814, Percy Shelley was paying frequent visits to

Godwin, and had struck up a friendship with his daughter, Mary. He sought in

her the commonality of interests and the intellectual companionship that was

missing in his marriage to Harriet. Initially, Percy’s relationship with his

wife was initially a happy one, but Percy was a selfish man, and very

self-absorbed. Harriet was very devoted to raising their children, and didn’t

pay him or his writing career the kind of attention that he wanted.

Consequently, Percy looked for that companionship and sympathy elsewhere, and

found it in Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin. As the daughter of William Godwin and

Mary Wollstonecraft, she was a revolutionary, a poet, an intellectual; all

qualities that Percy felt were lacking in his wife.

Mary also had her

reasons for being attracted to Percy. By that time, Percy had become a central

figure in the Godwin household. William Godwin was dependent upon him not only

for intellectual stimulation and emotional sympathy, but also for financial

support as Percy was giving him massive amounts of money in order to alleviate

his poverty. Mary also saw in Percy her ideal man: a young, passionate,

deeply-committed poet who shared her love for her father.

Mary and Percy began a

romantic relationship with each other while Percy was still married to Harriet.

Mary’s father, William Godwin, discovered their relationship, and forbade them

from seeing each other again. His principled opposition to marriage and support

of free love did not extend to his own daughter. Mary initially tried to do as

her father wished, but, after Percy threatened to commit suicide if he could

not be with her, she realised that she needed to pursue their relationship. As a

result, Mary and Percy eloped to France, with Mary's stepsister, Jane

Clairmont, in tow. The young couple could not get married, however, because

Percy was still legally wed to Harriet. This was Percy's second elopement, as

he had also eloped with Harriet three years before. Upon their return several

weeks later, the young couple were dismayed to find that Godwin refused to see

them. He did not talk to Mary for three and a half years.

Mary consoled herself with her studies and with Percy, who set himself up in the roles of tutor and mentor as well as lover to the young woman. He drew up a programme of study in literature and languages that Mary followed diligently throughout their first few years together. Percy, too, was more than satisfied with his new partner during this period. He exulted that Mary was "one who can feel poetry and understand philosophy," and he enjoyed discussing literary and political issues with her.

Nonetheless, the

couple's life together was not idyllic. Percy's father, Sir Timothy Shelley,

disapproved of his son's abandonment of his pregnant wife and his relationship

with Mary Shelley, and cut off his son's allowance as a result. By that time,

Percy was deeply in debt as a result of his own profligate spending habits and

the generous loans that he had made to William Godwin among other individuals.

He spent several months on the run from his creditors and apart from Mary.

At the same time, Mary

was beginning to realise that Percy's all-consuming focus on the intellectual

and abstract meant that he tended to be narcissistic and self-centred, and that

he was frequently unaware of or indifferent to the impact of his actions and

demands on the people around him. For instance, as part of his commitment

to free love, Percy Shelley attempted to set up a radical community of friends

who would share everything in common, including sexual partners. Around the

central relationship between himself and Mary, he tried to set up secondary

sexual relationships between himself and Claire Clairmont, and Mary and his

best friend Thomas Hogg. Mary was distressed by this turn of events, as she had

hoped that Percy would provide her with the stable family and sense of

belonging that she had always desired. Moreover, although Mary was fond of

Thomas Hogg as a friend and companion and reciprocated his attentions, she was

not sexually attracted to him, and refused to sleep with him. Her pregnancy

with her first child may have influenced her decision not to engage in a sexual

relationship with another man as well. Her relationship with her step-sister

Claire had also deteriorated by that point, and she wanted Percy to send her

away from their household, but he refused to compromise his vision of how his

community should be organised.

Even more devastating

for Mary, however, were the events surrounding the birth and death of their

first child, Clara, in February 1815. Born two months

prematurely, Clara was a sickly child and was not expected to live.

Nonetheless, Percy left Mary to nurse the child on her own and to entertain

Thomas Hogg, while he went on walks and errands with Claire, and consulted the

doctor for his own weak heart. When the child died early in March, Mary fell

into a deep depression, yet Percy was again indifferent to her and spent more

time with Claire than his primary partner.

Mary bore the couple's

second child on 24 January 1816, a boy whom the couple called William after her

father. This time, the pregnancy went smoothly, and William

grew to become a favourite of the household, earning the nickname

"Lovewill" for his beauty and his charm. His father took a greater

interest in him than he had in Clara, although scholars like Anne K. Mellor

have argued that it was largely a narcissistic one as Percy hoped to raise

the child in his own image.

Trip to Switzerland and Frankenstein

In May 1816, the couple

and their son travelled to Lake Geneva in the company of Claire Clairmont.

Their plan was to spend the summer near the famous and scandalous poet Lord

Byron, whose recent affair with Claire had left her pregnant. From a

literary perspective, it was a productive and successful summer. Percy began

work on "Hymn To Intellectual Beauty" and "Mont Blanc";

Mary, in the meantime, was inspired to write an enduring masterpiece of her

own. Forced to stay indoors one evening because of cold and rainy weather, the

group of young writers and intellectuals, enthralled by the ghost stories from

the book Fantasmagoriana, decided to have a ghost-story

writing contest. Byron and Percy Shelley abandoned the project relatively

soon, with Byron publishing his fragment at the end of Mazeppa. In her

preface to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein, Mary claims that he

had a terrible idea about a skull-headed lady who was punished for peeping

through keyholes. Mary herself had no inspiration for a story, which was a

matter of great concern to her. However, Luigi Galvani's report of his 1783

investigations in animating frog legs with electricity were mentioned

specifically by her as part of the reading list that summer in Switzerland. One

night, perhaps attributable to Galvani's report, Mary had a waking dream;

she recounted the episode in this way: “My imagination, unbidden, possessed and

guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness

far beyond the usual bounds of reverie…I saw the pale student of unhallowed

arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together—I saw the hideous phantasm

of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show

signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half-vital motion…What terrified me

will terrify others; and I need only describe the spectre which had haunted my

midnight pillow.” This nightmare served as the basis for the

novel that she entitled Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus

(1818).

Return to

England

Returning to England in

September 1816, Mary and Percy were stunned by two family suicides in

quick succession. Mary's older half-sister, Fanny Imlay, left the Godwin

home and took her own life at a distant inn. Percy's first wife, Harriet,

drowned herself in London's Hyde Park. Discarded and pregnant, Claire had not

welcomed Percy's invitation to join Mary and himself in their new household.

Shortly after Harriet's

death, Percy and Mary were married, now with Godwin's

blessing. Their attempts to gain custody of Percy's two children by Harriet

failed, but their writing careers enjoyed more success when, in the spring of

1817, Mary finished Frankenstein.

Over the following

years, Mary's household grew to include her own children by Percy, occasional

friends, and Claire's daughter, Allegra Byron, by Byron. Shelley moved his

family from place to place first in England and then in Italy. Mary suffered

the death of her infant daughter Clara outside Venice, after which her young

son Will died too, in Rome, as Percy moved the household yet again. By now

Mary had resigned herself to her husband's self-centred restlessness and his

romantic enthusiasms for other women. The birth of her only surviving child,

Percy Florence Shelley, consoled her somewhat for her losses.

Eventually the group

moved to Lerici, a fishing village in Italy, but it was an ill-fated choice. It

was here that Claire learned of her daughter's death at the Italian convent to

which Byron had sent her, and that Mary almost died of a miscarriage,

being saved only by Percy's quick thinking. And it was from there, in July

1822, that Percy was caught in a storm while aboard a boat at sea, and

drowned.

Later life

Mary was tireless in

promoting her late husband's works, including editing and annotating

unpublished material. Despite their troubled later life together, she revered

her late husband's memory and helped build his reputation as one of the major

poets of the English Romantic period. On 1 February 1851, Mary Shelley died at

the age of 53 from a brain tumour. She is buried in St. Peter's Church,

Bournemouth, Dorset, England.

The

Birth of Frankenstein

In her novel, Mary Shelley is silent on just how

Victor Frankenstein breathes life into his creation, saying only that success

crowned "days and nights of incredible labor and fatigue." Frankenstein offers no monster-making

recipes. But Shelley's story did not

arise from the void. Scientists and physicians of her time, tantalized by the

elusive boundary between life and death, probed it through experiments with

lower organisms, human anatomical studies, attempts to resuscitate drowning

victims, and experiments using electricity to restore life to the recently

dead.

A Physical

Dissertation on Drowning, 1747

Rowland Jackson (d. ca. 1787)

National Library of Medicine Collection

When

Percy Shelley's first wife, Harriet, drowned in London in 1816, rescuers took

her lifeless body to a receiving station of the London Society. There, smelling

salts, vigorous shaking, electricity, and artificial respiration--as with the

resuscitation bellows --had been used since the 1760s to restore drowning

victims to life. Harriet, however, did not survive.

Restored

to Life?

In March 1815, Mary Shelley dreamed of her dead

infant daughter held before a fire, rubbed vigorously, and restored to life. At the time, scientists

would not have wholly dismissed such a possibility. Could the dead be brought

back to life? Could life arise spontaneously from inorganic matter? Physicians

of the day treated such questions seriously--as the treatises they wrote, the

methods they employed, and the contrivances they built all testify.

Blundell's Gravitator

Pennsylvania State University Libraries

James

Blundell, a London physician troubled by the many women who died after

childbirth from massive bleeding, introduced blood transfusion between humans, using

the simple apparatus shown here. Reproduction of an illustration from The

Lancet, 1828-1829.

Galvanism

During the 1790s, Italian physician Luigi Galvani

demonstrated what we now understand to be the electrical basis of nerve

impulses when he made frog muscles twitch by jolting them with a spark from

an electrostatic machine. When Frankenstein was published, however,

the word galvanism implied the release, through electricity, of

mysterious life forces. "Perhaps," Mary Shelley recalled of

her talks with Lord Byron and Percy Shelley, "a corpse would be

reanimated; galvanism had given token of such things."

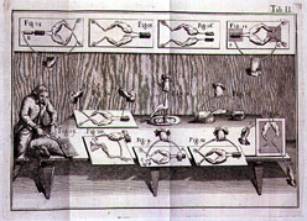

Galvani's

Experiments

National Library of Medicine Collection

Illustration of Italian

physician Luigi Galvani's experiments, in which he applied electricity to frogs

legs; from his book De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari (1792).

A

Galvanized Corpse

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Electricity's seeming ability

to stir the dead to life gave the word galvanize its own special flavoring, as

this 1836 political cartoon of a "galvanized" corpse suggests.

Alchemy

In the history of science, alchemy refers

to both an early form of the investigation of nature and an early philosophical

and spiritual discipline, both combining elements of chemistry, metallurgy,

physics, medicine, astrology, semiotics, mysticism, spiritualism, and art all

as parts of one greater force. Alchemy has been practiced in Mesopotamia,

Ancient Egypt, Persia, India, and China, in Classical Greece and Rome, in the

Muslim civilization, and then in Europe up to the 19th century—in a complex

network of schools and philosophical systems spanning at least 2500 years.

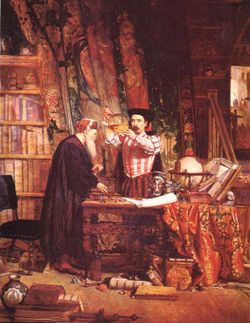

"The

alchemist", by Sir William Fettes Douglas, 1853

Alchemy as a philosophical and spiritual discipline

The best known goals of

the alchemists were the transmutation of common metals into Gold or Silver, and the creation of a "panacea," a remedy that

supposedly would cure all diseases and prolong life indefinitely. In the

Middle Ages, European alchemists invested much effort on the search for the

"philosopher's stone", a legendary substance that was believed

to be an essential ingredient for either or both of those goals. The

philosopher's stone was believed to mystically amplify the user's knowledge of

alchemy so much that anything was attainable. Alchemists enjoyed prestige and

support through the centuries, though not for their pursuit of those goals, nor

the mystic and philosophical speculation that dominates their literature.

Rather, it was for their mundane contributions to the "chemical"

industries of the day—the invention of gunpowder, ore testing

and refining, metalworking, production of ink, dyes, paints, and cosmetics,

leather tanning, ceramics and glass manufacture, preparation of extracts and

liquors, and so on. To alchemists, however, all of their discoveries in the

scientific fields of physics and chemistry were only important as metaphors for

a higher spiritual truth that was the real point of their investigations. In

the Middle Ages, some alchemists increasingly came to view the spiritual

aspects of their studies as the true foundation of alchemy; the chemical substances,

physical states, and material processes that they discovered were seen as mere

metaphors for more important spiritual things. Alchemists used the literal

meanings of their alchemical formulas about chemicals and physics to hide their

spiritual teachings, which were at odds with the Medieval Church. If the

alchemists had not been secretive about their real studies, the church would

have arrested them all and burned them at the stake as heretics during the

Inquisition.

The symbolic meaning of

what alchemists do is therefore more important than just seeking a cure for all

sicknesses in the panacea, or turning base metals into gold. Both

the transmutation of common metals into gold and the universal panacea actually

symbolized evolution from an imperfect, diseased, corrupt state of being

towards a perfect, healthy, incorruptible and everlasting state of being; and

the philosopher's stone then represented some mystical key that would make this

evolution possible. In practising alchemy, the alchemist wasn’t really

looking for gold or a cure for cancer; he was seeking out the highest kind of

wisdom.

Again, alchemists had to

be careful about what they were doing because it was heretical, and if they

were caught by the Church, they’d be burned alive. This is why alchemists wrote

everything in secret codes, using cryptic alchemical symbols, diagrams, and

textual imagery. Their weird writings typically contain multiple layers of

meanings, allegories, and references to other equally cryptic works; and must

be laboriously "decoded" in order to discover their true meaning.

In his Alchemical Catechism, Paracelsus

clearly denotes that his usage of the metals was a symbol:

|

“ |

Q. When the Philosophers speak of gold and silver,

from which they extract their matter, are we to suppose that they refer to

the vulgar gold and silver? A. By no means; vulgar silver and gold are dead,

while those of the Philosophers are full of life. |

” |

Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus, also known as Saint Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne,

was a Dominican friar who achieved fame for his comprehensive knowledge and advocacy

for the peaceful coexistence of science and religion. He is considered

to be the greatest German philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages. He

was the first medieval scholar to apply Aristotle's philosophy to Christian

thought at the time. Catholicism honors him as a Doctor of the Church, one of

only 33 men and women with that honor.

Biography

He was born sometime

between 1193 and 1206. He was called “magnus” meaning “great” because of his

immense reputation as a scholar and philosopher. The great Catholic Church

philosopher and theologican Thomas Aquinas studied under Albertus. In 1260, the

Pope made him Bishop of Regensburg. Albertus is frequently mentioned by Dante,

who made his doctrine of free will the basis of his ethical system. In his

Divine Comedy, Dante places Albertus with his pupil Thomas Aquinas among the

great lovers of wisdom in the Heaven of the Sun. Albertus is also mentioned,

along with Agrippa and Paracelsus, in Mary Shelly's Frankenstein, where

his writings serve as an influence to a young Victor Frankenstein. Albertus

was beatified in 1622. He was canonized and officially named a Doctor of the

Church in 1931 by Pope Pius XI.\

Writings

Albertus' writings

displayed his prolific habits and literally encyclopedic knowledge of all sorts

of topics. He was perhaps the most widely read author of his time.

Albertus' activity was more philosophical than theological.

Albertus's knowledge of

physical science was considerable and for the age remarkably accurate. His industry in every department was great, and though we find in his

system many gaps which are characteristic of scholastic philosophy, his

protracted study of Aristotle gave him a great power of systematic thought

and exposition. His scholarly legacy justifies his contemporaries' bestowing

upon him the honourable surname Doctor Universalis.

In the centuries since

his death, many stories arose about Albertus as an alchemist and magician. On the subject of alchemy and chemistry, he wrote treaties on Alchemy;

Metals and Materials; the Secrets of Chemistry; the Origin of Metals; the

Origins of Compounds, and a Concordance which is a collection of Observations

on the philospher's stone; there is scant evidence that he

personally performed alchemical experiments.

According to legend,

Albertus Magnus is said to have discovered the philosopher's stone and

passed it to his pupil Thomas Aquinas, shortly before his death. Magnus

does not confirm he discovered the stone in his writings, but he did record

that he witnessed the creation of gold by "transmutation."

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Cornelius

Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius

Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486-1535) was a German

magician, occult writer, astrologer, and alchemist. He was born to nobility in

1486. In 1509, he taught at the University of Dole in France, but was denounced

at the university for teaching Jewish thought. Agrippa’s masterpiece, De

occulta philosophia libri tres, was a kind of collection of early modern

occult thought. There is no evidence that Agrippa was seriously accused, much

less persecuted, for his interest in or practice of magical or occult arts

during his lifetime, apart from losing several teaching positions.

After Agrippa's death,

rumors circulated about his having summoned demons. In

the most famous of these, Agrippa, upon his deathbed, released a black dog

which had been his familiar. This black dog resurfaced in various legends about

Faustus, and in Goethe's version became the "schwarze

Pudel" Mephistopheles. The latest literary manifestation seems to be

the Grim from the Harry Potter series.

In the nineteenth

century, Mary Shelley mentioned him in some of her works. In her gothic novel

Frankenstein, Agrippa's works were read and admired by Victor Frankenstein. In

her short story The Mortal Immortal, Agrippa is imagined as having

created an elixir allowing his apprentice to survive for hundreds of years.

Agrippa also receives

mention in the first of J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series, Harry Potter

and the Philosopher's Stone. On Harry's first journey aboard the

Hogwarts Express train, Ron Weasley tells Harry he is missing two cards from

the complete set of collectible 'famous witches and wizards' cards found inside

boxes of Chocolate Frogs. The cards he is missing are Ptolemy and Agrippa.

Writings

Agrippa is perhaps best known for his books. Here

is an incomplete list:

- The Speech Attacking the Uncertainty and Vanity of the Sciences and

the Arts, 1526; a skeptical satire of the sad state

of science.

- Declamation on the Nobility and Preeminence of the Female Sex, 1529; a book on the theological and moral superiority of women.

- Three Books About Occult Philosophy;

this is a collection of occult and magical thought, and is Agrippa's most

important work. Agrippa argued that the natural world was linked to the

celestial and the divine through magic. Agrippa proposed a magic that

could resolve all problems raised by the tension between faith and

knowledge, and thereby validate the truth of Christian faith.

Paracelsus

Paracelsus was an alchemist, physician, astrologer, and general occultist. Born

Phillip von Hohenheim, he later took up the name Philippus Theophrastus

Aureolus Bombastus von Hohenheim, and still later took the title Paracelsus,

meaning "equal to or greater than Celsus", a Roman encyclopedist from

the first century known for his tract on medicine.

Biography

Paracelsus was born and

raised in Switzerland. As a youth he worked in nearby mines as an analyst. At

the age of 16 he started studying medicine at the University of Basel, later

moving to Vienna. He gained his doctorate degree from the University of

Ferrara.

Paracelsus rejected the

magic theories of Agrippa; Paracelsus did not think of himself as a magician

and scorned those who did, though he was a practicing astrologer, as were most,

if not all of the university-trained physicians working at this time in Europe.

Astrology was a very important part of Paracelsus' medicine. In his Archidoxes

of Magic Paracelsus devoted several sections to astrological talismans for

curing disease, providing talismans for various maladies as well as talismans

for each sign of the Zodiac. He also invented an alphabet called the Alphabet

of the Magi, for engraving angelic names upon talismans.

Paracelsus pioneered the

use of chemicals and minerals in medicine. He

performed experiments on the human body. His thought that sickness and health

in the body relied on the harmony of man with Nature. He took an approach

different from those before him, using this analogy not in the manner of

soul-purification but in the manner that humans must have certain balances of

minerals in their bodies, and that certain illnesses of the body had chemical

remedies that could cure them. He summarized his own views: "Many have

said of Alchemy, that it is for the making of gold and silver. For me such is

not the aim, but to consider only what virtue and power may lie in

medicines."

Paracelsus gained a reputation for being arrogant,

and soon garnered the anger of other physicians in Europe. His fellow doctors became angered by allegations that he had publicly

burned traditional medical books.

Paracelsus died in 1541

in Salzburg, and was buried according to his wishes in the cemetery at the

church of St Sebastian in Salzburg. His remains are now located in a tomb in

the porch of the church.

Paradise Lost

Paradise

Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the

17th-century English poet John Milton. The poem concerns the Judeo-Christian

story of the Fall of Man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by Satan and

their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Milton's purpose, stated in Book

I, is "to justify the ways of God to men" (l. 26) and to examine the

conflict between God’s foresight and human free will.

The protagonist of this

epic is the fallen angel, Satan. Looked at from a modern

perspective it may appear to some that Milton presents Satan sympathetically,

as an ambitious and proud being who defies his tyrannical creator, omnipotent God,

and wages war on Heaven, only to be defeated and cast down. Indeed, William

Blake, a great admirer of Milton and illustrator of the epic poem, said of

Milton that "he was a true Poet, and of the Devil's party without knowing

it". Some critics regard the character of Lucifer as a precursor of the

Byronic hero.

The story is innovative

in that it attempts to reconcile the Christian and Pagan traditions:

like Shakespeare, Milton found Christian theology lacking, requiring something

more. He tries to incorporate Paganism, classical Greek references and

Christianity within the story. He greatly admired the classics but intended

this work to surpass them.

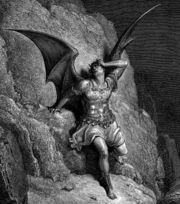

Lucifer, the main protagonist of Paradise Lost, as drawn by Gustave Doré.

Milton's story contains

two plot-lines: one of Satan and another of Adam and Eve. Lucifer's story is an

homage to the old epics of warfare. It begins after Lucifer and the other rebel

angels have been defeated and cast down by God into Hell. In Pandæmonium,

Lucifer must employ his rhetorical ability to organize his followers; he is

aided by his lieutenants Mammon and Beelzebub. At the end of the debate, Satan

volunteers himself to poison the newly-created Earth. He braves the dangers

of the Abyss alone in a manner reminiscent of Odysseus or Aeneas.

The other story is a

fundamentally different, new kind of epic: a domestic one. Adam and Eve are

presented for the first time in Christian literature as having a functional

relationship while still without sin. They have passions, personalities,

and sex. Satan successfully tempts Eve by preying on her vanity and tricking

her with semantics, and Adam, seeing Eve has sinned, knowingly commits the same

sin by also eating of the fruit. In this manner, Milton portrays Adam as

a heroic figure but also as a deeper sinner than Eve. They again have sex,

but with a newfound lust that was previously not present. After realizing their

error in consuming the "fruit" from the Tree of Knowledge,

they fight. However, Eve's pleas to Adam reconcile them somewhat. Adam goes

on a vision journey with an angel where he witnesses the errors of man and the

great Flood, and he is saddened by the sin that they have released through the

consumption of the fruit. However, he is also shown hope – the possibility of

redemption – through a vision of Jesus Christ. They are then cast out of

Eden and an angel adds that one may find "A paradise within thee,

happier farr." They now have a more distant relationship with God,

who is omnipresent but invisible (unlike the previous tangible Father in the

garden of Eden).

The Contents

of the 12 Books are:

Book I: In a long, twisting opening

sentence, the poet invokes the "Heavenly Muse" and states his theme,

the Fall of Man, and his aim, to "justifie the wayes of God to men".

Satan, Beelzebub, and the other rebel angels are described as lying on a lake

of fire, from where Satan rises up to claim hell as his own domain and delivers

a rousing speech to his followers ("Better to reign in hell, than serve in

heaven").

Book II: Satan and the rebel angels debate whether or not to conduct

another war on Heaven, and Beelzebub tells them of a new world being built,

which is to be the home of Man. Satan decides to visit this new world, passes

through the gates of Hell, past the sentries Sin and Death, and journeys

through the realm of Chaos. Here, Satan is described as giving birth to Sin

with a burst of flame from his forehead, as Athena was born from the head of

Zeus.

Book III: God observes Satan's journey and foretells how Satan will

bring about Man's Fall. God emphasizes, however, that the Fall will come about

as a result of Man's own free will and excuses Himself of responsibility. The

Son of God offers himself as a ransom for Man's disobedience, an offer which

God accepts, ordaining the Son's future incarnation and punishment. Satan

arrives at the rim of the universe, disguises himself as an angel, and is

directed to Earth by Uriel, Guardian of the Sun.

Book IV: Satan journeys to the Garden of Eden, where he observes Adam

and Eve discussing the forbidden Tree of Knowledge. Satan, observing their

innocence and beauty hesitates in his task, but concludes that "...reason,

honour and empire..." compel him to do this deed which he "should

abhor." Satan tries to tempt Eve while she is sleeping, but is discovered

by the angels. The angel Gabriel expels Satan from the Garden.

Book V: Eve awakes and relates her dream to Adam. God sends Raphael to

warn and encourage Adam: they discuss free will and predestination and Raphael

tells Adam the story of how Satan inspired his angels to revolt against God.

Book VI: Raphael goes on to describe further the war in Heaven and

explains how the Son of God drove Satan and his minions down to Hell.

Book VII: Raphael explains to Adam that God then decided to create

another world (the Earth), and he warns Adam again not to eat the fruit of the

Tree of Knowledge, for "in the day thou eat'st, thou diest;/ Death is the

penalty imposed, beware,/ And govern well thy appetite, lest Sin/ Surprise

thee, and her black attendant Death".

Book VIII: Adam asks Raphael for knowledge concerning the stars and the

heavenly orders; Raphael warns that "heaven is for thee too high/ To know

what passes there; be lowly wise", and advises modesty and patience.

Book IX: Satan returns to Eden and enters into the body of a sleeping

serpent. The serpent tempts Eve to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. She

eats and takes some fruit for Adam. Adam realizes that Eve has been tricked,

but eats of the fruit. In their loss of innocence Adam and Eve cover their

nakedness and fall into despair: "They sat them down to weep, nor only

tears/ Rained at their eyes, but high winds worse within/ Began to rise, high

passions, anger, hate,/ Mistrust, suspicion, discord, and shook greatly/ Their

inward state of mind."

Book X: God sends his Son to Eden to deliver judgment on Adam and Eve,

and Satan returns in triumph to Hell.

Book XI: The Son of God pleads with God on behalf of Adam and Eve. God

declares that the couple must be expelled from the Garden, and the angel

Michael descends to deliver God's judgment. Michael begins to unfold the future