http://www.readersdigest.ca/mag/2000/12/lesra_martin.html

The Metamorphosis of Lesra Martin

BY LYNNE SCHUYLER

Lesra martin lived in

Life in Hell

STICKY, humid heat clung to Lesra Martin as he

sat next to his father, Earl, on the subway. Neither spoke as the grimy train

clattered and swayed, rushing towards Greenpoint, a

white section of

Lesra,

15, stared at the unfamiliar cityscape rolling past. He was anxious, but not

about his new job.

Lesra,

15, stared at the unfamiliar cityscape rolling past. He was anxious, but not

about his new job.

The skinny, malnourished tenth

grader knew only the world of his neighbourhood, a

few city blocks that more resembled a war zone than a community. Bushwick, one of

The skinny, malnourished tenth

grader knew only the world of his neighbourhood, a

few city blocks that more resembled a war zone than a community. Bushwick, one of

Even walking to school was perilous. At the first sound of shots, Lesra had learned to duck behind the tires of the nearest parked car or flatten himself in a doorway. He had some protection: His older brother Fru, a gang member already in trouble with the law, told others that Lesra was off-limits. But rival gangs staked out entire city blocks; it was a place where blacks like Lesra lived on one side, and poor whites and Hispanics on the other.

Now, crossing into Greenpoint, unfamiliar territory, Lesra was nervous. "You mind your p's and q's," Earl cautioned in his low, raspy voice.

Lesra

stared at his father's shaking hands. Their lives hadn't always been like this.

He had dim memories of a different life, of a house in

In the 1960s Earl had worked as a factory foreman. The family shared lots of special times. Alma, Lesra's mother, used to crank their living-room stereo to full volume, grabbing her babies by the hand and dancing with them. Sometimes they went up to the Apollo Theatre to see performers like James Brown scorch the stage.

But overnight, it seemed, their lives abruptly shifted due to a series of humiliating setbacks. A severe back injury left Earl disabled. They lost their house in a fire; at times, they were homeless, stranded in shelters or with relatives. The Martins slid into poverty, ending up in Bushwick. By then, both Earl and Alma had severe drinking problems, and their lives disintegrated into endless late-night arguments that disturbed their hungry children's sleep.

LESRA pushed his fears

aside and tried to listen as his father pointed out the stops he'd have to

remember to return home. The 15-year-old willingly shouldered a heavy

responsibility. Five of his seven siblings had left home, but the rest of his

family, housed in a decaying tenement, depended on every cent he earned. The

family's welfare cheque was exhausted long before

month's end, and it wasn't unusual for the household of five to go a week with

very little food.

Lesra had been nearly 11 when their lives hit rock bottom. Hungry, wanting to help out, he walked into a local store one day and, uninvited, began bagging groceries. The manager shooed him out, but the feisty kid kept returning until they let him stay. Customers took to the good-natured, pint-size boy who lugged their groceries home. On good days he pocketed $2 or $3 in tips, enough to buy rice and beans for his family.

A likable kid with a bright smile, Lesra had a knack for drawing people to him. Still, it wasn't enough to protect him from the random violence always at hand. His mother feared Lesra would not survive the streets if he didn't toughen up. "Men aren't allowed to cry," she constantly told him. Yet Lesra hated fighting; it was a last resort when nothing else worked. In the neighbourhood he earned the moniker The Diplomat for his ability to talk his way out of trouble. That didn't stop two neighbourhood toughs, brothers, from zeroing in on Lesra. One time, the younger brother raced out of his house with a bow and arrow and shot Lesra in the chest. Furious, Lesra thrashed him. He had his wound dressed at school but knew this wouldn't be the end of it.

After school the older brother, now joined by a big, menacing cousin, stood outside Lesra's house. "Get out here, punk!" the brother screeched. "What'sa matter -- you scared?"

In the house, Lesra paced the floor, fearing not only the two boys outside but his older brother's fury inside. "You gotta fight or you'll be branded a sissy," Fru raged. "If you don't go out there, I'll beat you up."

He reluctantly stepped outside,

hoping he could talk his way out of trouble. "Your brother stabbed me in

the chest!" he said, yanking up his shirt to show the wound.

He reluctantly stepped outside,

hoping he could talk his way out of trouble. "Your brother stabbed me in

the chest!" he said, yanking up his shirt to show the wound.

But the two weren't buying it. The brother punched Lesra's wound while the cousin jumped him. As they tore into him, Lesra backed into a fence, hoping to gain an advantage. But they overpowered him, getting in a few more licks before they raced off.

Lesra stumbled to his feet, boiling over with fury. He chased after them and tackled the brother, whacking him over the head with a garbage can lid. Then he clipped the cousin on the side of his ear. Howling in pain, the pair limped off.

The brawl left him shaken, but nothing frightened him as much as the power of his own anger. He knew he could easily have killed one of the kids. With Fru in and out of jail, it seemed only a matter of time before Lesra followed in his footsteps.

By the time he was 13, Lesra was fast becoming hardened. Repeated harassment from gang members forced him to tuck an unloaded gun into his pants one day. He fanned it around at school, hoping it would make the others back off. By 15, he was feeling the pressure to join a gang.

Now, as the subway train screeched into the station, Lesra had no way of knowing how profoundly his life was about to change.

The

Canadians

IN THE MIDDLE of that July

1979, Canadians Terry Swinton, 32, Sam Chaiton, 28, and several housemates had traveled to the Greenpoint Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lab to

research a gas-saving pollution device. They were part of a group of eight

university friends who, in the 1960s, joined resources and became successful

entrepreneurs. All shared a strong social conscience, mixing business with

activism and compassion for anyone less fortunate. They owned a house in

At the EPA lab, Lesra's infectious grin and raw energy soon caught the

attention of Chaiton and Swinton.

Lesra and William Fuller, another ghetto youth hired

at the lab, spent their workdays playfully punching, chasing and spraying each

other with water instead of the taxis they were supposed to wash. Whenever Lesra saw the Canadians, his face would light up. "Yo,

"I'm gonna be a lawyer," Lesra cheerfully told them one day, confiding his ambitions. "Lawyers make lots of money from people in trouble, and where I live, someone's always in trouble."

Listening, Swinton

and Chaiton sensed Lesra

didn't have the faintest idea what a lawyer actually did. Privately, they

speculated that he was more likely to need a lawyer than to become one.

Listening, Swinton

and Chaiton sensed Lesra

didn't have the faintest idea what a lawyer actually did. Privately, they

speculated that he was more likely to need a lawyer than to become one.

The Canadians returned

to

In

"

In mid-August, Terry

and Sam returned to

What could be more interesting than the fun we're having? he wondered.

Lisa began reading to

him from Claude Brown's Manchild in the

Promised Land. Lesra stopped goofing around and

sank into a chair, mesmerized by the story of a

Lesra was euphoric when the Canadians invited him to spend ten days with them later in the month. This time, Lesra's return to Bushwick was even more difficult: In Toronto, for the first time in his life, he had felt safe.

For their part, the Canadians had formed a close emotional bond with the boy. They were deeply troubled by the gaps in his schooling and worried for his survival in a neighbourhood where drugs, jail or gangs were the only options.

A bold plan took hold:

Why not bring Lesra to

The eight members of the group wrestled with the idea. Was it fair to take Lesra from his family, who loved and depended on him? "Once he leaves, it'll be hard for him to go back," Peters pointed out. If he came, they agreed, the entire household would invest their energy and resources in helping him realize his potential.

One afternoon in September, African-American poet James McRae, a co-worker at the EPA lab and a friend of the group, sat in the Martins' tiny living room. Lesra nervously watched as McRae explained the Canadians' proposal. McRae reassured the Martins that the Canadians weren't taking Lesra away; he would be back for summers and holidays. "It would be a shame to pass up an opportunity like this," he said. "Nothing is more vital than access to a decent education."

His parents were

perplexed by this generous offer. Lesra saw the pain

in his mother's eyes, yet he desperately wanted to go. Agitated, uncertain,

A few days after

McRae's visit, the Canadians flew Earl Martin to

"Well, boy, you can if you want to," his father said, clearly satisfied that his son would be in good hands.

A Different World

LESRA arrived in

Their first goal was to tackle his health problems. They watched in astonishment as Lesra heaped sugar on his meat and vegetables. Haunted by years of hunger, he squirreled away bread and fruit in his room. "There will always be plenty of food in the fridge," Lisa gently told him.

Back home, doctors were only for desperate emergencies. As a consequence, Lesra had lived in pain for years. He suffered from a sinus infection, constant headaches, stunted growth and poor vision. The Canadians spent months shuttling him to doctors, specialists and a dentist to improve his health.

Carefully they drew him into a larger world by reading books and newspapers out loud, by watching TV news, by asking his opinion during business discussions. Everything provided fodder for learning.

One day they sat on

the grass at the

At first the Canadians guessed that Lesra was no more than a few grades behind. They talked about enrolling him in Grade 9, perhaps with some extra tutoring.

"Read this," Sam said one day, sliding a book into Lesra's hands.

Lesra fumbled to pronounce the words. Sam watched as his eyes skittered over the page, desperately searching for words he recognized, like "cat."

"What's this word, and this?" Sam repeatedly asked, pointing to the text.

Stumped and unwilling to admit it, Lesra searched his memory for words he knew or made up the words as he went along, growing more frustrated and angry.

Suddenly it dawned on Sam that Lesra could neither read nor write; they had greatly overestimated his level of education. A subsequent reading test placed him at a Grade 2 level. Lesra was shattered. He had attended school faithfully, easily passing from grade to grade. If he couldn't read or write, what had been the point of his going?

Chaiton had tutored Lisa Peters' son Marty, who was severely dyslexic. It seemed natural that he could teach Lesra as well. Lesra was bright, but his lack of Standard English -- the key to learning everything else -- was a huge obstacle. Lesra's speech was a complicated mix of street slang, broken English, even triple negatives. He pronounced words like "beauty" as "bruty."

The first year, Sam stripped everything down to the basics, tackling phonetic skills first. None of it made sense to Lesra. "That's not the way I was taught in school," he argued. Once proud of his class standing, he soon became convinced that he was incapable of learning.

"I'm stupid. There must be something wrong with me," he frequently told Sam, tears streaming down his face. Such moments were heartbreaking for Sam. "No, Lesra, it's not your fault," he said. Often their lessons veered off into discussions of personal issues as Lesra battled deeply ingrained feelings of inferiority.

For Lesra, school had been a safe haven where he could sleep, get warm, have something to eat. Tests that challenged a student's knowledge were almost nonexistent. Kids played cards at the back of the class while teachers read newspapers. Lesra had never been assigned homework or asked to write an essay or to read a book. "That's why you didn't learn," Sam explained.

Many days ended with both of them physically and emotionally exhausted. "I can't do this!" Lesra would shout, storming up to his room and throwing his clothes into a bag. He wanted to quit, go home. Sam and the others would leave him alone to cool down. Then a couple of them would go up to his room to talk and to ask him how he'd explain to his family that he'd given up. So Lesra would calm down and begin the struggle to learn all over again.

In truth, Lesra enjoyed learning and didn't want to leave. The household was a stimulating bustle of activity, a place where learning never stopped.

Trips home, however, were a painful reminder of the staggering extremes between his two worlds. On one visit to Bushwick, he was strolling down the block with his younger brother Elston when police cars screeched to a halt near them. Trunks popped open, guns were yanked out, and the police stormed a nearby building. Lesra, 16, and Elston, 14, hit the ground as bullets whizzed over their heads. Lesra reached for his brother's hand, certain they wouldn't survive. The siege ended as abruptly as it started, but Lesra was furious that anyone had to live like this.

Even more painful was the toll his absence seemed to take on his family. It was expected the eldest brother at home would always look out for his younger siblings. With Fru in and out of jail, that responsibility had fallen on Lesra's shoulders.

"Why did you leave?" Elston would ask during his visits. "All the pressure to take care of the family is on me now."

Elston's frustration posed a terrible dilemma for Lesra. The rest of his family was supportive, never pressuring him to come home. He knew his younger brother looked up to him and followed his ways. The close-knit pair were a lot alike -- taking responsibility and trying to be fair and decent to others.

"I wouldn't have left if I didn't think you could do it," Lesra told his brother, proud that Elston tried hard to fill his shoes.

On every flight back

to

Yet he couldn't forget his family. Lesra cut lawns, raked leaves, shovelled snow -- all to earn money to send home. His family's hardships were harsh reminders of his need to become educated, to stay out of the ghetto.

Revelation

WHEN HE'D first moved to

To dispel Lesra's misconceptions, the Canadians encouraged Lesra to study the past, emphasizing black heroes and black

American history. One summer day in 1980, Sam handed Lesra

a thick book by Frederick  Douglass, a brilliant black American human-rights leader. "You

can read this out loud to us," Sam said.

Douglass, a brilliant black American human-rights leader. "You

can read this out loud to us," Sam said.

"It's like a foam [phone] book!" Lesra retorted. The dense volume, written in 1857, was laced with difficult words and Victorian phrases but told of Douglass's own struggle with literacy. Terrified, Lesra flipped it open, his eyes raking over the text. Haltingly, he stumbled over the words. Tears welled up in his eyes. He slammed the book shut and glared at Sam and Terry.

"You can do it," Sam insisted. "You've got the skills to handle this. This is where the payoff is for all the work you've been doing."

Lesra remembered his mentors telling him not to stop at troublesome words, but to read the whole sentence and paragraph so that the meaning would become clear. He sounded out the words, working his way through the text. A flicker of recognition crossed his face. The words, the paragraphs, everything suddenly made sense to him.

Not long afterwards,

at a used book sale, Lesra's eyes fell on The

Sixteenth Round: From Number 1 Contender to #45472. The fierce looking man

on its cover was the author, Rubin "Hurricane" Carter. The famous

middleweight boxer had been tried and imprisoned for the 1966 murders of three

white people in

Hungrily he read Carter's story, published in 1974. The passion behind Carter's words and the force of his language bore into Lesra's mind and heart. The book was filled with profanity, language he had heard every day on the streets of Bushwick. That in itself was a revelation: He didn't know anyone could write as they spoke or felt in real, everyday life. As Carter's story unfolded, Lesra experienced the anger, frustration and helplessness the boxer felt over his wrongful conviction.

Until then, Lesra had looked at life as one insurmountable hurdle after another. Yet here was Carter, after years of insufferable conditions, never wavering in his resolve to prove his innocence.

Lesra thought about Carter all the time, resolving to work harder at his studies. If Carter could not be broken, then surely he could overcome his own fear of reading and writing.

One day he carefully smoothed out some paper on his desk, then picked up a pen to write Carter a letter. He struggled to find the words to express his thoughts and feelings. Soon, balls of crumpled-up paper surrounded the wastebasket as he scratched out his thoughts. Finally he folded a letter and slipped it into an envelope.

A Single Letter

AT NEW JERSEY'S Trenton State Prison in September 1980, Rubin Carter barely glanced up when a guard propped a single letter between his cell's bars. Every day, mail arrived from people begging for autographs or asking to write his story. Appalled, he never opened them.

After his second trial and imprisonment in 1976, continuing to steadfastly maintain his innocence, Carter kept himself apart from the routine of prison life. I'm not a criminal, and I'm not participating in this system, he thought bitterly, refusing to wear prison garb and eating only food shipped in by a friend. Disillusioned, forgotten by the politicians and celebrities who had once rallied to his cause, he shunned visitors for nearly five years, refusing to let anyone but his lawyers see him in the "lowest pits of hell."

Now, the solitary letter nagged at him for hours until he finally ripped it open.

"Dear Mr. Carter," it began. It was the first letter Lesra Martin had ever written, and in it he told Carter about his home in Bushwick, his new life with the Canadians and his belief in Carter's innocence.

WEEKS

after he'd mailed his letter, Lesra haunted the

front-door mail slot, waiting for a reply. Finally, a white envelope with

The innocence and energy in Lesra's letter had touched a profound chord in Carter. Through Lesra, he felt a pure joy that he hadn't known in years. Soon letters flowed back and forth between Carter and Lesra and the Canadians.

On the last Sunday in December 1980, while home visiting his family, Lesra set out for Trenton State Prison. At the forbidding stone walls, lined with gun towers and barbed wire, Lesra's heart pounded with excitement over seeing Carter and with sheer terror over entering the ominous structure. Fru's been in jail, he thought, and I'd probably be here too if not for the Canadians.

It took more than an hour for him to pass through a series of screenings, sign-ins and security checks. Finally he stood in the prison's former death house, now used as a visiting area and still showing the braces where the prison's electric chair once stood.

The other visitors and prisoners paired off until Carter and Lesra, who was shaking with fear, were the only two people left standing.

"You must be Lesra!" Carter boomed in a deep, rich voice. He'd known of Lesra's intention to visit, but had not encouraged it. The death house was a degrading place for prisoners and those who came to see them.

Lesra had expected to find the Carter of his photos: the formidable, shaven-head boxer with the ferocious stare. Instead, Carter, not much taller than Lesra, greeted him with a broad grin. Sensing Lesra's fear, Carter crushed the teenager to him in a protective, fatherly hug. Lesra immediately felt safe.

As they sat laughing and talking, Lesra turned over the contradictions in his mind. From Carter's own book, Lesra knew he was no choir boy; Carter had been in and out of trouble before his murder conviction.

Still, that was no reason for

him to be in jail for something he didn't do. He's survived this place and

yet he's so gentle, Lesra thought in amazement.

His every instinct told him that Carter was innocent.

Still, that was no reason for

him to be in jail for something he didn't do. He's survived this place and

yet he's so gentle, Lesra thought in amazement.

His every instinct told him that Carter was innocent.

Their visit drew to an end, and both sat in silence, Carter's warm hand resting on top of Lesra's. It was the first outside human contact Carter had had in years.

They both looked up as another prisoner approached.

"Mr. Carter, would you like a picture of you and your son?" the man asked, noticing the affection between the two. Pleased, and not bothering to correct him, Carter nodded. The pair stood, arms clasped around each other, and Lesra beamed.

Miscarriage of Justice

ARRIVING back in

As they learned more about his case, the Canadians were convinced there'd been a terrible miscarriage of justice. They sent him gifts of food and clothing, but they could provide little more than moral support as Carter's lawyers pushed through legal appeals on his conviction.

"How's your schooling going?" Carter asked in every phone call to Lesra. Learning, he patiently told Lesra, was not only a way to express himself but a means to take control of his life. Carter was intensely proud of Lesra and showed his school essays to other prisoners.

Inspired by Carter, Lesra worked hard, earning high marks in his correspondence courses and, later, in an English night-school course. He routinely sent his marks to Carter. "What happened to the other two points?" Carter queried when Lesra received 98 percent on one of his papers. Lesra chuckled. Like Sam Chaiton, Carter expected him to do well. Yet for every step forward, another crisis always pulled him back.

In the fall of 1981, he picked up the phone one day to hear his father's voice, dejected, slurred. "I have some bad news," Earl said. Listening, Lesra sank into a chair sobbing. Devastated, he passed the phone to Terry.

The gifts he regularly sent home were prized by his family. But a knitted cap sent to Elston had been stolen, resulting in a fight that had gone too far: Fru accidentally killed another man while trying to get it back. Guilt ridden and in shock, he had waited for the police to arrive.

Lesra

wanted to go back and help his family, but the Canadians convinced him it was

better to stay. Unable to concentrate on his work, he was sick at heart for weeks

afterwards, anguished that his gift had caused someone's death. Fru would later be sentenced to five to 15 years  for manslaughter.

for manslaughter.

THROUGHOUT 1982 the Canadians spent months studying Carter's case, reviewing

court transcripts, tracking every detail in testimony. They tacked papers to

the walls, sorting and analyzing the mountain of information. Aided by Carter,

they compiled a one-by-three-metre chart of

witnesses, noting every discrepancy in their testimony, then

sent it to Carter's lawyers, hoping it would somehow be useful in an appeal in

U.S. Federal Court.

Then in November there came another blow: Carter cut off all contact with the Canadian household. He had lost another round of appeals, and in despair of ever being released, he stopped writing and phoning.

For Lesra, it was torturous to think of Carter lost in despair.

To ease his mind and heart, Lesra focused on his

studies, finishing Grade 13, while preparing to enter the

Smiling, Sam proudly told him, "The next one you frame will be your university degree!"

Lesra carefully packaged copies of his diploma and the acceptance letter from the University of Toronto, mailing a set to his parents. They were very proud; he was the first in his family to attend university. Lesra quietly sent the other copies to Carter, the only way he could say "thanks" for the role Carter had played in his success.

Renewed Effort

EIGHT months after Carter had cut off contact with the group, he phoned the Toronto house again. This time his call, in late summer 1983, was to ask for help. The Canadians, inspired by Carter's continued fight, told him that no matter how long it took, they would fight alongside him to help secure his release from prison.

To finance their efforts, the friends sold their Toronto house and moved into a smaller place. Chaiton, Swinton and Peters even moved to New Jersey to be closer to Carter, while Lesra stayed behind to attend school and help with the group's home-renovation business. The trio would devote the next five years, and contribute hundreds of hours of time and energy, to Carter's case.

They researched more than 15 years worth of legal documents and evidence, and helped draft legal briefs that would be used to seek a writ of habeas corpus from a Federal Court judge, demanding that authorities justify the incarceration. In Carter's case, the writ alleged prosecutorial misconduct, suppressing evidence and improperly introducing a theory of racial revenge into the trial. If it failed, all avenues of freedom would be closed and Carter would spend the rest of his life in prison.

IN SEPTEMBER 1983 Lesra entered the University of

Toronto. He had dropped the idea of becoming a lawyer, soured on a system that

would allow Carter to be imprisoned unjustly.

He decided instead to major in anthropology and sociology. Listening to the other students, he was secretly pleased that he could speak and write as well as they did. Chaiton had taught him well.

But instead of drinking in the success of his academic achievements, he was haunted by self-doubt. On the outside he appeared articulate and confident, but inside, his old fears were never far away. The ghetto was around every corner. Once, leaving a campus building, he opened the door and thought he saw not the lush school grounds but the scarred streets of Bushwick.

Midyear, he was assigned to write a political philosophy paper on social justice issues. He knew how to research his papers, yet he found himself frozen with fear. His mind churned in panic as his deadline approached. The night before his paper was due, he sat down to write, snatching ideas from the top of his head. He was shocked when his paper was praised as "original" and later considered for publication. That paper became a talisman, something he would look back at whenever his confidence failed him.

By 1985 Lesra was working full-time in the renovation business, rising at 6:30 a.m, putting in a full day, then rushing off to night-school courses and doing homework. He longed to be in New Jersey, helping his friends work on Carter's case. When he could, he researched trial transcripts, often dashing down to New Jersey for weekend visits.

Freedom

YEARS of exhaustive work by Carter, his lawyers and the Canadians paid off in November 1985 when Federal Court Judge Lee Sarokin overturned the 1976 convictions, citing grave "constitutional violations." He ruled that Carter's conviction, and that of his codefendant John Artis, was based on "racism rather than reason, and concealment rather than disclosure" by New Jersey prosecutors.

After 20 years in prison, Rubin Carter was at last set free. The miraculous outcome left Lesra overwhelmed with joy.

Emotional upheavals at home, however, continually tugged at his heart. Both of his parents had developed cancer, and Earl suffered seizures from a brain tumour. Lesra saved his money and, in the summer of 1986, brought them to Canada on a rare visit. He bought a new suit for his father and new shoes and a white chiffon dress for his mother on her birthday.

Struck by Lesra's self-assurance, Alma proudly gazed at her son. "You've become a real man," she told him. She had been tough on him while he was growing up, preparing him for the world she thought he would have to live in, but it had created a gulf between them that had hurt Lesra deeply. Now, though, he finally understood his mother. His leaving had brought them closer together.

One night at the house, Lesra tucked his frail parents into bed. Shortly afterwards, Earl reappeared. "I want to give you something," he said quietly, motioning his son to follow him upstairs. Curious, Lesra followed, then sat on the edge of his parents' bed.

Earl cleared his throat, then slowly, gently hummed and sang a song he'd written for his son. It was called "The End is Near."

Lesra felt his eyes brimming with tears. His father had rarely talked about his long-lost hopes for a singing career, and Lesra sensed that he was deeply ashamed of how his life had turned out. This was a truly special gift from Earl.

That fall of 1986, Lesra, now 23, took stock of his life. Carter, along with Chaiton, Swinton and Peters, was living in New York, responding to legal appeals that would drag on for another 26 months. Like the rest of the household, Lesra had carried a big load, going to school and working in the group's business to help finance Carter's case. He felt drained and wanted some time for himself.

So Lesra struck out on his own, moving into an apartment near the university.

Taking Stock

IN APRIL 1988 Lesra was studying for his final exams when he was jarred by the ringing of his phone. It was Lori, his older sister; their mother had been hospitalized with severe abdominal pains. He rushed home.

In New York Lesra sat by Alma's hospital bedside, stroking her hand as he stared into the worried faces of his family. He stayed several days, and when Alma appeared to regain her strength, he returned to Toronto. A few days later she passed away. Devastated, he buried himself in studying for his final exams, anything to avoid grieving.

On a mild day in September, Lesra set out on a 19-hour drive to Dalhousie University in

Halifax, where he planned to study for his master's degree in anthropology. For

the first time in eight tumultuous years, he had hours and hours to think. His

life had been a series of extraordinary events unfolding at breathtaking speed:

his life in the ghetto, the struggle to read and write, the fight to free Carter,

his mother's death. Now his father was dreadfully ill with cancer. Everything

had taken its toll.

On a mild day in September, Lesra set out on a 19-hour drive to Dalhousie University in

Halifax, where he planned to study for his master's degree in anthropology. For

the first time in eight tumultuous years, he had hours and hours to think. His

life had been a series of extraordinary events unfolding at breathtaking speed:

his life in the ghetto, the struggle to read and write, the fight to free Carter,

his mother's death. Now his father was dreadfully ill with cancer. Everything

had taken its toll.

He felt the weight of unspoken expectations -- the likelihood of someone from Bushwick making it this far were slim to none. Yet he had. The future suddenly frightened him. What if he failed?

He finally understood what an

unselfish decision his mother had made that day in 1979 when she asked Earl to

decide. It was a bittersweet memory. He was proud of his parents, yet saddened

they would not share in his success. Why am I doing this? What difference

does it make now?

He finally understood what an

unselfish decision his mother had made that day in 1979 when she asked Earl to

decide. It was a bittersweet memory. He was proud of his parents, yet saddened

they would not share in his success. Why am I doing this? What difference

does it make now?

He pulled off the road, exhausted by the emotions crowding his head. He closed his eyes and tears slid down his cheeks.

Headed for a new life in Halifax, he had everything in the world to look forward to. Instead, he felt hollow inside.

LESRA'S years of illiteracy still shaped every decision he made. He rushed headlong into the demanding course load for his master's degree. Not long after his arrival in Halifax, he befriended a young woman at school. Longing for some kind of stability, he married her in the spring of 1989.

Shortly afterwards, in May, his father passed away. Once again, Lesra blunted his grief with work, turning to his sister Lori for solace.

His pace never slackened. Every time he passed Dalhousie's law school, a lump burned in his throat. That's where I should be, he now thought. It remained an unfulfilled dream and he decided to act. He was accepted at law school in 1990 and figured he'd juggle that with his master's degree.

But by the following spring, Lesra felt his life spinning out of control. He had somehow squeezed in a full-time job between his classes, working night shifts. Running at breakneck speed throughout his day, he barely found time to crack open his books.

He was never home and his marriage -- complicated and unhappy -- unravelled. Miserable, he was forced to take a hard look at his life. Nothing he started ever got completed. Work on his master's degree had fallen by the wayside. Tackling law school before he was ready left him unable to focus. He made the painful decision to withdraw, before he lost that dream, too.

Lesra soon realized his downward slide had begun with the death of his parents. He had lost his sense of purpose. He resolved to complete his masters degree and one day return to law school.

Two years later, in 1993, Lesra handed in his master's thesis, prepared to delay his plans for law school after learning he'd been accepted into the University of Toronto's sociology doctorate program.

Rekindled Desire

ON A FREEZING, snowbound day in February 1994, Lesra pulled up to his doorstep in Toronto. As he got out of his car, he was startled to see Rubin waiting and shivering in a Jeep. "Lez, I need a place to stay," he said, stepping out to give Lesra a big hug.

In the years since his release, Carter had lectured, written and travelled in the United States, living on and off with the Canadians. Now, waylaid by snowy weather on his way back to the States, he decided to stop over at Lesra's apartment, then continue on the next morning.

They had seen little

of each other in recent years, each going his own way. As they sat talking the

next day, Lesra realized he wanted to spend more time

with Carter. Yet he worried about derailing his  goals, taking on too much. But suddenly he blurted out, "Why

not stay for a while?"

goals, taking on too much. But suddenly he blurted out, "Why

not stay for a while?"

The next few weeks, they discussed the idea of working together. They moved out of Lesra's flat and into a larger home. Lesra grew to appreciate Carter hollering "son" as soon as he stepped through the door.

Once, on a flight back from giving a speech, a flight attendant mistook them for father and son. Carter turned to Lesra and made a surprising revelation. "I told your parents I would take care of you if anything happened to them. I'd be honoured if you accepted me in that role."

Lesra was deeply touched.

He continued to work on his doctoral degree, and together he and Carter wrote, lectured and traveled, sharing their remarkable journey with others. Carter became the executive director of The Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted, a volunteer organization formed to address the problem of wrongful convictions internationally. On behalf of the organization, they researched cases, and Lesra's interviews with lawyers and judges rekindled his desire to be a part of the legal system.

One chilling visit to death-row inmate Rolando Cruz left Lesra deeply unsettled. Bleak and menacing, the Illinois prison was set high on a precipice. The clang of cell doors, Cruz's hands and feet shackled in chains, the vivid sights and smells, reminded Lesra of his first prison visit with Carter. Afterwards, as their car wound down the hill from the prison, Lesra slumped in his seat, emotionally drained.

He remembered how horrifying it had felt to leave Carter behind. It was no different with Cruz. Eventually, Cruz would be cleared and freed, but for Lesra, the helplessness he felt that day only added fire to his desire to return to law school.

Everything he had ever wanted was happening. He was pursuing his doctorate and working with Carter. Yet if he didn't pursue his dream, he would always wonder if he'd made the right choices. Returning to Toronto, he reapplied to law school. But that meant leaving Carter.

Beating the Odds

WHEN LESRA returned to Nova Scotia in September 1994, he was no longer afraid of what lay ahead. Now 31, he was on a mission, more clear and focused on his goals than ever before. He immersed himself in his studies and joined several student associations. At one meeting in the fall of 1995, he noticed a slender young woman with delicate features who seemed just as curious about him.

Who is this guy? Cheryl Tynes, 28, wondered when she heard him speak. Private and reserved, she was drawn to his warmth, confidence and outgoing nature. They became instant friends. As they spent long hours together studying for their grueling law exams, they discovered many similarities in their backgrounds. Both were from large, poor families living in racially tense neighbourhoods, and both valued education as a way to succeed in life.

One wintery day in January 1996, Lesra confided to Cheryl that he was attracted to her, but she brushed him off. "You're not in my five-year plan," she told him bluntly, afraid her own hard-won goals would be disrupted.

Lesra heeded her feelings and didn't call for weeks. But one day he phoned to say "hi," catching her off guard. Cheryl couldn't hide her excitement at hearing his voice again.

By April Lesra had finished his second year of law school. Needing a break, he met his sister Lori in New York, then traveled with her back to her South Carolina home. Late one afternoon, they telephoned Elston. The siblings laughed and talked for hours. Lesra hung up and looked at Lori, his eyes sparkling. "Let's surprise Elston with a visit!" he grinned, and they made plans to go back to New York.

That night, however, as Lesra settled on Lori's couch, the phone rang. It was his younger brother Damon. His voice broke as he told Lesra that Elston had been shot and killed on the streets of Harlem.

Lesra staggered to his feet. Dazed, he lurched into Lori's room. Too shocked to speak, he handed Lori her bedside phone.

"No, no, no!" she sobbed.

In the hours that followed, they learned what had happened. A niece had argued with a man at a nightclub. She called home and Elston left to pick her up. Getting out of his car, Elston asked his niece what happened. A patient man, he liked to rock back on his heels and cross his arms when he listened to others. As he lifted his arms to fold them over his chest, the man who'd argued with his niece fired, hitting Elston.

His brother's senseless death wounded Lesra even more deeply than the deaths of his parents. Elston was the man Lesra would have been had he stayed in Bushwick, trapped by a lack of education. Violence defined their neighbourhood, yet Elston was a gentle man who worked and raised his family, never troubling anyone. Grief stricken and haunted by guilt, thinking he should have been there instead of Elston, Lesra felt he had lost a part of himself.

Lesra drew closer to Cheryl as she helped him cope with his sorrow on his return. Her compassion made him realize how much he loved her. In 1998, a year after he graduated from law school, they married.

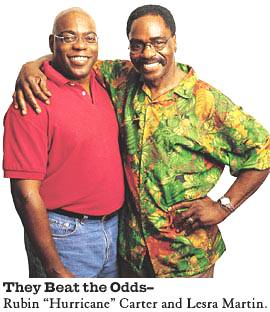

Lesra articled with a Vancouver law firm and a year later moved to Kamloops to work in the Crown counsel's office. In May 1999 he stood in an oak-panelled room of the Kamloops courthouse, his black robes swirling about him. Family and friends packed the courtroom, smiling and crying as the newly called lawyers rose to take their oath before a B.C. Supreme Court judge. Carter sat next to Cheryl, his eyes alive with pride and love. He had never dreamed that Lesra would be the catalyst upon which his own freedom rested. Now he was watching yet another miracle take place. He and Lesra had both beaten the odds.

"The Hurricane"

THIS PAST January Lesra and Cheryl found themselves on a plane to New York. They were going to attend a United Nation's special screening of The Hurricane, the movie dramatization of the events surrounding Carter's release from prison. Bushwick, a place that once held no hope or future, was only a subway ride away from the UN, an irony not lost on Lesra.

As he worked during the flight on a speech he was to deliver to the UN, the tears wouldn't stop. Lesra felt as if he had come full circle. He was back in his parents' living room, waiting for their decision that would allow him to leave. For him their sacrifice was heroic.

He remembered how complete strangers had made a commitment to help him better his life, then kept that promise. He wondered if Elston would still be alive had he been given access to a proper education, too. He wondered how many other kids were in places like Bushwick, their promise held back by illiteracy.

He knew that when he stood before the UN delegates, he would have a story to tell: How compassion, courage and hope can change lives forever.

THE RELEASE of the movie The Hurricane has proved to be another

life-changing event for Lesra. In demand as a lecturer,

he has taken a leave of absence from his Crown prosecutor's job and speaks

passionately about the issues surrounding literacy.

"I'll always be a lawyer," he says. "But right now I can make more of an impact speaking about the importance of education, the freedom I found in reading and the value of learning.

"I'll never forget where I came from. I'm still on a journey -- I'll be on it for the rest of my life."